VANISHING POINT

February 18 — April 15, 2016

TO AUTUMN.

1.

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o’er

-brimm’d their clammy cells.

2.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep,

Drowsed with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cider-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings, hours by hours.

3.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The redbreast whistles from a garden-croft,

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

John Keats

1795 - 1821

GODS AND MONSTERS FROLICKING UNDER THE TREES in their bountiful Edens; the utopian landscape has been a subject of art since the ancient Greeks. In Western art, the landscape has occupied the greater or lesser part of the background of a depiction, yet the focus was always on the figure (ourselves). By the end of the 15th century, through the work of Giorgione and Titian, landscape was increasingly integrated into painting. Still, it remained the setting for human or supernatural activity. It was the Dutch who did away with the human presence in landscape art and made it the sole subject of a painting. As styles of landscapes evolved they were elevated from the lower position in the hierarchy of genres (just above that of animal and still life painting) to that of high art by the inclusion of historical, classical or religious subjects. Painting that was the product of the artist’s imagination commanded the greatest attention from the public and the academies. For example, Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) would ennoble his landscapes with the fanciful addition of historical or mythological figures to serve the expectations of high art.

The 19th century saw the concept of the pure landscape take hold fully. In Europe, the Romantic school found inspiration in wildness and with atmospheric effects. The Hudson River School following the European Romantics, tried to depict the hugeness and grandeur of the new America as the country began expanding its political power. Then the Impressionists pulled it back in and began looking at how fleeting light affected the moment. From Impressionism onward, art and the landscape became evermore conceptual.

ABOVE: In 1859,The Heart of the Andes by Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) captivated audiences when it was exhibited for the first time in New York City. Over 12,000 people paid twenty-five cents each to view the five feet high, almost ten feet wide painting that established Church as the preeminent landscape painter in the US.

With Vanishing Point, Art House Gallery is looking at the ways contemporary artists are portraying the landscape now. The natural environment has lost none of its draw to artists, but unlike in past eras, there is no dominant school to dictate the approach an artist should take.

Gillian Wainwright brings us back to the 19th century with her referencing of Impressionism in “Orange Streak”. The dominance of the brush stroke and the reliance on color and light retain the immediacy of the fleeting moment. Michael Ensminger also gives us an impression of the landscape, but with a more conceptual view. His “Early Morning Drift” is both a comment on environmentalism through the reuse of a paper bag as the support of the work, while the texture and form of the embroidery references drifting snow as it falls and accumulates.

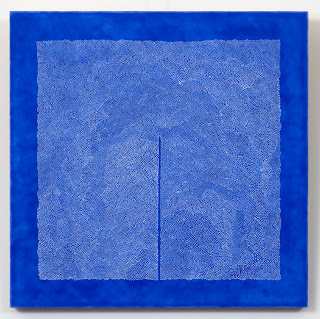

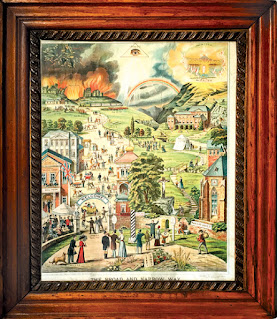

Casey Inch with “Ravine” and M. Benjamin Herndon with “Untitled” are both commenting on overpopulation and urban sprawl as they contribute to the disappearance of wilderness. Inch, by whitening out the landscape painting, declares that the 19th century Romantic ideal of the grand wilderness of the expanding country has reached a crisis of depletion and encroachment. As we strive to reuse and recycle, still we continue to expand and overpopulate. Herndon sees his print as a meditation on harmonizing these dichotomies of human existence in nature.

Michael Dal Cerro’s, “The Provisional City” and Sarah Nicole Phillips’, “Office Solution” both make comments on the urbanization of the landscape. Dal Cerro sees the man-made environment as an Escherian maze of towers and tunnels that threatens to consume the globe until the only way left is up, while Phillips envisions the time when our sterile, cubicle dominated workspaces revert back to the wilderness we are only just holding back.

Sara Sutro and Elin Noble both take a more Zen, abstract approach to nature. Sutro’s “Landscape Composite” celebrates the changing color of the land/sky horizon at dawn or dusk. Noble’s work in silk, “Danube 3”, is a meditation on the fluidity and movement of water.

Both Anthony Santella and Robert Lach have narrowed their focus away from the expansive view of nature and concentrated on the microcosm. Lach takes his forms from an insect’s architectural design, and also incorporates materials from the landscape with “Nest Colony II”. Santella has enshrined in his Wardian case a bit of the earth itself creating his own tiny, mobile landscape that seems set to scurry off to find new ground.

Amber Heaton sets her sights on our place in the universe with her works “All the Sunlight” and “All the Moonlight”, where she tracks the changes in the placement of the sun and moon from her spot in Brooklyn. These drawings map our place as the earth travels through space with its constant companions, the life-giving sun and the tide-making moon.

We only have one earth, and we may be alone with our life in the universe. Vanishing Point is part of that constant awareness that we must cherish the uniqueness of that life and the natural beauty that surrounds us on our planet. There is no other.

Arthur Bruso & Raymond E. Mingst

curators

THE ARTISTS:

Nicole Antebi, Lasse Antonsen, Nancy Cohen, Ian Costello, Michael Dal Cerro, Michael Ensminger, Amber Heaton, M. Benjamin Herndon, Casey Inch, Tom Koken, Ellen Kozak, Sahar Kubba,

Robert Lach, Dominic Montuori, Elin Noble, Gilda Pervin, Sarah Nicole Phillips, Anthony Santella, Robin Sherin, Sarah Sutro, Gillian Wainwright, Debra Weisberg

Vanishing Point was presented through Art House Productions.